Esteemed journalists,

Good afternoon.

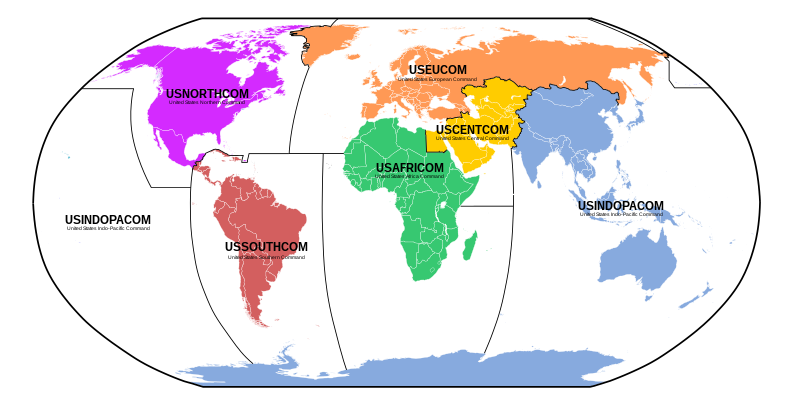

Thank you for responding to our invitation. We considered it important to discuss today problems of European and, hence, global security. In Europe, NATO’s members are increasingly claiming global domination. The alliance has already declared the Indo-Pacific region a zone of its responsibility. Events on our continent are of interest not only to the Europeans or residents of North America but also to representatives of all countries, primarily the developing nations who want to understand what initiatives the NATO states, which have declared their global ambitions, can draft for their regions.

Why did we decide to hold this news conference today? The event that used to be called the OSCE Ministerial Council opened in Lodz today. This is a good reason to see what role this organisation has played since its establishment.

The Helsinki Final Act was signed in 1975 and was qualified as the greatest achievement of diplomacy of the time, a harbinger of a new era in East-West relations. Nevertheless, the number of problems kept piling up. Now the OSCE has amassed a huge amount of problems. They have a deep historical projection that is rooted in the late Soviet period, the 1980s and 1990s when the number of missed opportunities exceeded all possible expectation of even the most pessimistic analysts.

Let’s recall the year 1990 – the anticipation of the end of the Cold War. Many even declared the end of it at that time. The world was expected to focus on universal values and receive “the dividends of peace.” A summit of the organisation that was called then the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was also held that year. During that summit, the participants, including the NATO and Warsaw Treaty members, adopted a Charter of Paris for a New Europe that announced that “the era of confrontation and division of Europe has ended” and declared the elimination of barriers for building a truly common European home without dividing lines.

It was 1990. You would think if everyone had made such sound declarations, what was it that prevented them from delivering on them? The point is the West had no intention of taking any steps to put these nice words and obligations into life. It could be said with confidence that the West at the time supported this type of slogans as it reckoned that our country would never again regain its positions in Europe, let alone in the world. The Westerners believed that it was “the end of history”, as they said at the time. From then on, everyone would live by the rules of liberal democracy, so they could relax and promise anything. Those attractive slogans ended up hanging in the air.

Here’s an interesting fact from that period. In 1990, at the closing stage of the CSCE Summit in Paris, US Secretary of State James Baker warned the US President that the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe might pose a real threat to NATO. I understand him – this is really so. When the Cold War was over, many sensible and farsighted politicians and political scientists said it would make sense if not only the Warsaw Treaty, which had ceased to exist by that time, but also the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was dissolved and if every effort was made to turn the CSCE into a genuine bridge between East and West, and into a single platform for achieving common objectives based on a balance of interests of all member countries.

This never happened. In reality, the West sought to maintain its dominance. Allowing the calls for equality and removing dividing lines and barriers, as well as for a genuine Common European Home to come true was seen by the Westerners as a threat to their position, which was to preserve the dominance of Washington and Brussels in all global affairs, primarily in Europe. This basic instinct that both the Americans and other NATO member countries never lost explains the policy of expanding NATO heedlessly, thereby eroding the main idea of the OSCE as a collective tool for ensuring equal and indivisible security, and makes all those beautiful documents that this organisation has approved since the 1990s worthless. It was of principal importance to the West to show who the master of the Common European Home was – a home that all [countries] had collectively undertaken to build. Essentially, this is where the notorious concept of a “rules-based order” is rooted. It was already at that time that the West regarded these “rules” as an indispensable element of its position in the world arena. This perception that the Western “rules” can resolve any problem without consulting anyone allowed the West to feel free to subject Yugoslavia to barbaric bombing for 80 days and to destroy its civilian infrastructure. Later, under a fictitious pretext, the Westerners invaded Iraq and bombed it destroying everything that civilians needed and that was essential for the life support system of the country. Next, Libya as a state was destroyed. Then followed many other risky ventures, which you know well.

We talk about the aggression against Yugoslavia because we can still feel its effects. It was a flagrant violation of the Helsinki principles. In March 1999, NATO, seeking to show that it can do whatever it wants, opened Pandora’s box by trampling underfoot the fundamentals of European security adopted by the OSCE.

Russia hoped that the Helsinki principles could be revived. We continued fighting for the OSCE. We proposed drafting a legally binding document, an OSCE Charter based on the Helsinki Final Act. The West did not accept our initiative.

Those who honestly believed that any issues should be settled on the basis of common European principles worked towards the adoption of a series of vital documents, including the Charter for European Security, in Istanbul in 1999. The Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) was adapted to the situation that developed after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. The CFE was drafted in the era of two military-political blocs, NATO and the Warsaw Treaty Organisation (WTO). When the latter was dissolved, the permissible number of the sides’ weapons coordinated in the context of the East-West confrontation no longer corresponded to reality, because many European countries were being drawn into NATO. After a series of difficult talks, the CFE was adapted, and the new text was signed in Istanbul in 1999. The adapted treaty was praised as the cornerstone of European security.

You know what happened to it. Trying to preserve the old document, the United States prohibited it allies from signing the adapted text, because the initial treaty provided legal grounds for NATO’s domination after the dissolution of the WTO. The United States subsequently pulled out of the ABM Treaty and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, as well as scrapped the Open Skies Treaty. The OSCE, although not completely indifferent to those changes, was unable to speak out in the treaties’ defence. The OSCE chairperson-in-office and secretary-general kept silent.

Another document adopted in Istanbul in 1999, the Charter for European Security, reads that no country should ensure its security at the expense of other states’ security. Nevertheless, NATO’s eastward expansion continued despite all the declarations adopted by all OSCE member states at the top level.

In 2010, Russia and other like-minded states, which did not lose hope of saving the organisation, adopted a declaration at the Astana summit, which said that security must be equal and indivisible, and that states should be free to choose alliances provided they do not try to strengthen their own security by weakening the security of others. The crucial formula is that no state or group of states have a right to claim pre-eminent responsibility for security in the Euro-Atlantic area.

If you have been following European developments in recent years, you will know that NATO has violated every one of its obligations. The alliance’s expansion created direct threats to the Russian Federation. The bloc’s military infrastructure moved closer to our borders, which ran counter to its commitments under the Istanbul Declaration of 1999. NATO stated unequivocally that the alliance alone could decide to whom it would provide legal security guarantees – that was also a direct violation of their Istanbul and Astana obligations.

We realised that NATO was simply ignoring those political declarations, thinking it was allowed to disregard them completely even though their presidents had signed those documents. In 2008, Russia proposed codifying those political declarations in order to make them legally binding. The proposal was declined, with the explanation that such legal guarantees in Europe could only be provided among NATO members. The alliance continued, absolutely consciously and knowingly, to pursue its thoughtless policy of artificial expansion with no real threats to NATO countries out there.

We remember the time when NATO was created. The first NATO Secretary General Hastings Ismay coined this formula: the purpose of NATO is “to keep the Soviet Union out [of Europe], the Americans in, and the Germans down.” What is happening now is nothing short of a return to the alliance’s conceptual priorities from 73 years ago. Nothing has changed. NATO is determined to keep the Russians “out,” while the Americans dream of keeping not only the Germans, but the whole of Europe “down” – and have in fact already enslaved the entire European Union. This philosophy of domination and unilateral advantages has not gone anywhere when the Cold War ended.

Over the time since the bloc was created, NATO has hardly been able to present a single real success story that would be to its credit. The Alliance brings devastation and suffering to those outside it. I have already mentioned its aggressions against Serbia and Libya, which led to the destruction of Libyan statehood; Iraq got added to the mix. Let’s also recall the latest example, Afghanistan, where the alliance unsuccessfully struggled to instil its version of democracy for 20 years. Security problems in the Serbian province of Kosovo have never been resolved, although NATO has been present there for more than two decades as well, and this fact is also telling.

Speaking of the US peacekeeping capabilities, look at how many decades the Americans have been trying to restore order in Haiti, which is a small country under their control. It is not Europe. There are numerous examples like this outside the European continent.

In 1991, NATO included 16 countries; now it has 30 members. Sweden and Finland are one step away from joining. The Alliance deploys its forces and military infrastructure ever closer to our borders, constantly building up its potential and capabilities, moving them towards Russia. They conduct manoeuvres and actually openly declare our country the adversary during exercises. NATO is intensifying its activities in the post-Soviet space. At the same time, it is laying claims to the Indo-Pacific region, and now also to Central Asia. All these aspirations to global domination are a direct and flagrant violation of the 2010 Lisbon Declaration, which was signed by all presidents and prime ministers of the North Atlantic bloc.

Until recently, we did everything in our power to prevent a further deterioration in the Euro-Atlantic Region. In December 2021, President Vladimir Putin made new proposals on security guarantees – a draft treaty between Russia and the US and a draft treaty between Russia and NATO. In this situation, seeing how determined the West was to drag Ukraine into NATO – it was an obvious red line for the Russian Federation, which the West had known about for years – we suggested that the Alliance stops expanding and wanted to reach an agreement on concrete, legally binding security guarantees for Ukraine, the Russian Federation, all European countries and all OSCE member states. The attempts to begin a discussion failed. We received the same response to all our calls to approach the situation in a comprehensive and creative way: that each country, and Ukraine first of all, has the right to join NATO and nobody can do anything about it. All components of a compromise formula about the indivisibility of security, that it should not be achieved at the expense of the security of other countries and that one organisation should not claim dominion in Europe, all of them were simply ignored.

In December 2021, Washington preferred not to take advantage of the opportunity for a de-escalation. And it was not only the United States, but also the OSCE, that could have facilitated a de-escalation of tensions if it had been able to settle the crisis in Ukraine based on the Minsk Package of Measures, which was agreed upon in February 2015 and unanimously approved by the UN Security Council resolution that same month. The executive structures of the organisation turned out to be completely subordinate to the US and Brussels, which set a course for comprehensive support of the Kiev regime’s policy of eradicating all things Russian: education, the media, the use of the Russian language in culture, the arts and everyday life. The Westerners also supported the Kiev regime when it sought to introduce the theory and practice of Nazism in its legislation: the relevant laws were adopted without any reaction from the “enlightened” capitals of Western democracies. Its efforts to turn Ukraine into a foothold for containing Russia, a territory of direct threats to our country also received support. These facts are well-known now. I want to note that the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, which has made its contribution to discrediting the OSCE in a blatant violation of its mandate, did not react in any way to the regular violations of the Minsk agreements by the Ukrainian armed forces and nationalist battalions.

The mission de facto took the side of the Kiev regime. After its activity was suspended, unseemly cases came to light of the mission’s interaction with the Western special services, as well as the participation of allegedly neutral OSCE observers in adjusting fire against the DPR and the LPR, and collecting intelligence data in the interests of the Ukrainian armed forces and nationalist battalions. They received information from the mission’s surveillance cameras installed along the contact line.

The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine put a lid on all these glaring problems, many of which you brought to light and made public although your editorial offices did not always permit this. The SMM deliberately turned a blind eye to all the violations, including preparations for a military solution to the problem of Donbass, which the Kiev regime was planning while Poroshenko and later Zelensky openly refused to honour the Minsk agreements. The West silently played along with these unacceptable activities. In mid-February 2022, the number of artillery attacks at the territory of the Lugansk and Donetsk people’s republics, which had gone on for years, increased tenfold. There is statistics that cannot be denied. A vast number of refugees flooded into Russia. This inevitably led to the recognition of the Lugansk and Donetsk people’s republics and in accordance with Article 51 of the UN Charter begin, at their request, the special military operation to save the people of Donbass from the Nazis and to eliminate security threats to Russia coming from Ukraine.

I would like to say that there is an explanation for this objectionable policy of the OSCE. Taking advantage of its numerical superiority in the organisation, the West has been trying to dominate it for years, or more precisely, to take over the last remaining platform for regional dialogue. The Council of Europe had already been maimed by the West without any chance of recovery. Today the OSCE is the target. Its powers and competencies are being eroded and spread out among narrow non-inclusive formats.

The EU has been working to create parallel structures and conferences, such as the European Political Community. On October 6, 2022, this forum held its inaugural meeting in Prague. When preparing that event and announcing the initiative of creating the organisation, President of France Emmanuel Macron proudly stated that all countries apart from Russia and Belarus had been invited to join. Prominent foreign policy officials such as Josep Borrell and Annalena Baerbock immediately picked up the tune, saying that a [European] security order should not be built together with Russia but against it, contrary to what Angela Merkel and other European leaders had called for. Other platforms are being created to force confrontational methods on the other countries in the spirit of the colonial mentality, and to spread the OSCE agenda among narrow formats, platforms, initiatives and partnerships.

A few years ago, Germany and France launched the Alliance for Multilateralism, a group where they planned to invite whomever they wished, and that initiative stabbed the OSCE in the back. In a similar way, the United States selectively invites participants to what it calls the Summit for Democracy. We asked the Germans and the French why they wanted to create that alliance when Europe already had the OSCE, which is an inclusive platform. The United Nations played the same role in global affairs – can any new format offer even more multilateralism than those? We asked, and we were told that while those formats indeed included all countries, for effective multilateralism, a group of leaders would be more suitable than the OSCE or the UN because those two platforms also included “retrogrades” that would hinder the progress of effective multilateralism. So it was up to those progressive leaders to advance it, while others would have to conform and follow – a philosophy that also undermines every high principle the OSCE has ever relied upon.

As a result of all this, the security space in Europe became fragmented, and even the OSCE is becoming a marginal entity, to put it mildly. The recent Chairmanships-in-Office have shown no interest in reversing this negative trend – quite on the contrary.

The Swedes presided in the OSCE in 2021, and even during that period, they stopped acting as “honest brokers,” but became active participants in the Western policy to subordinate the OSCE to the interests of the United States and Brussels. In fact, the Swedes paved the way to the OSCE’s funeral.

Throughout this year, our Polish neighbours have been diligently digging a grave for the organisation, destroying whatever was left of its culture of consensus. The decision on the role of the OSCE Chairmanship-In-Office, adopted by the OSCE Ministerial Council at its meeting in Porto as far back as in 2002, says the Chairmanship-In-Office should ensure that its actions are not inconsistent with positions agreed by all the participating States and that the whole spectrum of opinions of participating States is taken into account, which amounts to consensus. On November 23 of this year, the foreign ministers of six CSTO countries approved a statement expressing their principled assessments of the outrageous actions by the Polish Chairmanship-In-Office. We know that a number of other OSCE countries share this approach. It is important to say that Poland’s “anti-Chairmanship” will one day be seen as the most unsightly period in the OSCE history. No one has ever done so much damage to the OSCE while being at the helm.

For many years, the Western countries directed every effort towards hampering the development of an equal and indivisible European security system, contrary to the mantras they always repeated as political declarations. We are now reaping the fruit of this short-sighted and misguided policy. The letter and the spirit of the basic OSCE documents have been trampled upon. That organisation was created for a pan-European dialogue. I have already cited the goals proposed by the West and by the OSCE Chairmanships-in-Office this year and last year. All of the above raises difficult questions about what our relations with the organisation will be like. More importantly, what is going to happen to the OSCE itself? I think that if – or when, at some point in time – our western neighbours (there’s no getting away from this, we are neighbours) and our former partners suddenly become interested in resuming the joint work on European security, it won’t happen. That would mean going back to what we had before, but there would be no business as usual.

When, or if, the West realises the benefits of being neighbours and relying on some kind of a mutually agreed framework, we will listen to what they have to offer. Will there be an opportunity for such interaction in the foreseeable future? I don’t know. It’s up to the West, which has been systematically destroying every principle underlying the functioning of the unique pan-European organisation called the OSCE, all these long decades.

Question: Russia is now cut off from European diplomacy since Russian representatives were banned from attending OSCE meetings or the Munich Security Conference. What can Moscow do? How can it adapt to the new circumstances? How important is the grain deal for Russia in this context?

Sergey Lavrov: I can add to the above the fact that this year our parliamentarians were denied entry visas to the UK and, not long ago, to Poland and hence were unable to attend the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly meetings. This shows how the “honest brokers” run this pan-European organisation.

To follow up on whether we are being cut off from European diplomacy, we must first look into whether European diplomacy is still there, and if so, what is it like these days. So far, what we are hearing the key European diplomats say are Josep Borrell-like statements which he keeps repeating like a mantra since the outset of the special military operation that this war must be won by Ukraine “on the battlefield.” This is what a European diplomat is saying.

When President of France Emmanuel Macron announced a meeting as part of the European Political Community that he is promoting, he said that Russia and Belarus would not be invited to join it. EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell and German Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs Annalena Baerbock put forward yet another new goal: to build European security not with Russia, but against it.

If such statements are what European diplomacy is all about, I don’t think we need to be part of it. We should wait for rational people to show up there. Being vocal about the importance of ensuring Ukraine’s victory, President of the European Council Charles Michel insists that this must be done because Ukraine is striving for European values, and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg is claiming that it is already defending and promoting European values, freedom and democracy. Head of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen said something along these lines as well.

European diplomacy talking about the importance of helping Ukraine which upholds “European values” means only one thing: European diplomats are in the dark about multiple facts of what is really going on in Ukraine. They appear to be unaware of the fact that long before the special military operation began, the Russian Orthodox Church had been destroyed for years on end in violation of the rules of civilised life; ethnic minorities were unable to use their native languages in all aspects of everyday life without exception (later, European minorities were taken off that list, but Russian remained); Russian-language media was banned, and not only the media owned by Russian nationals and Russian organisations, but also Ukrainian-owned media outlets that broadcast in the Russian language; political opposition; political parties were banned; leaders of political organisations were arrested, and openly Nazi practices were enshrined in Ukrainian laws.

If, as it continues to use grand rhetoric to call upon everyone to defend Ukraine that is upholding European values, European diplomacy indeed is aware of what that country is in fact “promoting,” we do not want to be part of such diplomacy.

We will push to have this “diplomacy” end as soon as possible, and for the people who are pursuing hate-crazed policies in violation of the UN Charter, multiple conventions, and international humanitarian law to step down.

Numerous interviews with Vladimir Zelensky clearly show the kind of values the current Kiev regime is upholding. He never stops saying that “Russia must not be allowed to win.” Everyone applauds as if they are bound by a spell. In an interview, he said that if Russia were allowed to win (NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said it later as well), other large countries would feel they are within their right to attack smaller nations. Several large countries on different continents will reshape global geography. Vladimir Zelensky claims that he has a different scenario in mind where “every person on earth knows that no matter what country they live in and what kind of weapons they have, they enjoy the same rights and the same level of protection as everyone else around the world.”

None of the reporters who interviewed him got around to asking Mr Zelensky whether he remembered what he told the Ukrainians who felt they were part of the Russian culture to do. A year ago, in August 2021, he told them to “make off to Russia.” A person who is willing to protect the rights of every person in the world wanted to kick Russians out of his country only because they wanted to keep their language and culture. Perhaps, when he talked about everyone’s right to enjoy protection – “regardless of where they live”, the following public statement slipped his mind. In an interview in Kazakhstan, Ukrainian Ambassador to Kazakhstan Pyotr Vrublevsky said “We are going to kill as many of them as possible. The more Russians we kill now, the fewer will be left for our children to kill.” Not a single European diplomat commented on this statement, although we brought the untenable nature of this kind of conduct to their attention. This was an outright affront on the part of Zelensky’s regime to our Kazakh neighbours, who said it was unacceptable for the ambassador to make such statements. But this person spent a month in Kazakhstan after the incident before getting expelled. I pity European diplomacy which “swallows” this kind of approach to European values.

We issued multiple grain deal-related media releases. Since March 2022, our military have been announcing daily 12-hour humanitarian corridor windows for Ukrainian grain to be transported from Ukrainian ports. The only snag was that the ports were mined. Our Ukrainian colleagues were to navigate the ships through the minefields, while the Russian military were to guarantee safe delivery to the straits. Vladimir Zelensky claimed it was a “trap,” and that “Russians cannot be trusted.” Then we proposed guaranteeing freedom of passage across neutral waters in cooperation with our Turkish colleagues. They agreed. Zelensky started throwing tantrums again. The intervention of the UN Secretary-General made it possible to sign two documents in Istanbul on July 22. The first one clarifies the steps and guarantees that will apply when exporting Ukrainian grain from three Ukrainian ports. The second document is to the effect that the UN Secretary-General will strive to lift artificial barriers to Russian fertiliser and grain exports. A week ago, I heard someone from a European body say that the sanctions do not include restrictions on Russian fertiliser and grain exports, which is a blatant lie. There is no “fertilisers and food from Russia” segment in the sanctions lists. Banking transactions, primarily for our leading Rosselkhozbank, which has been cut off from SWIFT, are prohibited, though. Rosselkhozbank handles over 90 percent of our food supply-related transactions. Access to European ports for the Russian vessels and to Russian ports for foreign vessels, as well chartering or insuring them are prohibited as well. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres spoke about it openly at the G20 summit in Indonesia. He is in the process of having these barriers lifted. However, five months into the deal, the United States and the EU are responding woefully slowly. We have to work hard to obtain exceptions. We are supportive of what the Secretary-General is doing. However, the West is not showing much respect for his efforts. It’s their manner of letting everyone know who’s boss and who should be chasing whom and begging for things.

Question: What would European security look like without the Union State of Russia and Belarus? What is your forecast?

Sergey Lavrov: It is difficult to make any forecasts. I can only say for sure what the security of the Union State of Russia and Belarus will look like regardless of any future distortions of the OSCE foundation.

We know the worth of those who want to assume the OSCE chairmanship and promise to be an “honest broker,” the current leaders of the OSCE Secretariat who are not allowed to do anything outside the framework of their new concept. The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe was not set up in 1975 to force the member states to dance to any country’s tune and to accept a vision of the world and the security and cooperation goals formulated by our Western partners. The OSCE was established so that the voice of all countries would be heard, and no country would feel excluded from the common process. Everything has now been turned upside down. The West is doing what the OSCE was designed to prevent: it is digging dividing lines. But the ditches they are digging can also be used to bury somebody. I suspect that the target is the OSCE. All these initiatives, such as the European Political Community (all its member states apart from Russia and Belarus), an open invitation to destroy the OSCE and create in its place a Western hangout for promoting their projects, including illegal unilateral sanctions, and the creation of tribunals to confiscate other countries’ assets, all of this are the elements of a colonial mentality, which is still there. It is a desire and the striving to scavenge on others.

The United States is scavenging on Europe now. It will get richer off the economic and energy crises in Europe, sell its gas (at four times the price Europe paid for Russian gas), promote its own laws on combating inflation, and allocate hundreds of billions of dollars for its own industry to lure over investors from Europe. This will ultimately lead to Europe’s de-industrialisation.

The West is trying to create a security system without Russia or Belarus. They should start by coming to terms with each other. President of France Emmanuel Macron has flown to Washington to complain and demand. I don’t know what this will lead to, but we certainly do not need this form of security. Europe’s security amounts to total subordination to the United States. Several years ago, there were debates in Germany and France on the proposed “strategic autonomy” of the EU and the creation of an EU army. A US national security official said recently that Europe must abandon its dreams of an independent European army. Several years ago, such discussions led to the conclusion that Germany should rely on NATO to protect its security. Poland, the Baltics and several Central European states, which used to have a reasonable approach to the matter, now have ultra-radical Russophobic and anti-Europe governments.

As for Europe’s independence, discussions have been held on increasing the number of US troops for holding exercises near the borders of Russia and Belarus. When Pentagon chief Lloyd Austin was asked if the US troops would be deployed in Europe permanently or otherwise, he answered without a moment’s hesitation that Washington had not yet decided on the mode of its military presence in Europe. It never even crossed his mind to say that Washington would consult its European allies. We haven’t decided yet. This is their answer to the question about the form of security in Europe.

The Union State has military development plans. We also have a joint group of forces, which includes air and ground components. The presidents of Russia and Belarus are paying greater attention to this issue in the context of continuing Ukrainian provocations. We have taken the necessary measures to maintain our readiness for any turn of events. We will rely on the commendable capabilities of the Union State.

When Western Europe, NATO and the EU see the huge risks of their dead-end policies, we will look at what they can offer for negotiating with us.

Question: This month, NATO has held joint exercises in the Atlantic Ocean and in the Mediterranean Sea. It involved aircraft carriers from many countries, including the USS Gerald R. Ford, the lead ship of the US Navy, which took part in the drills for the first time. What is the United States’ role in NATO exercises? What is the goal of increased US military integration with Europe? What effect are NATO drills having on regional security in Europe?

Sergey Lavrov: Over the past decade, NATO exercises have become more intensive, frequent and openly aimed at containing Russia. They invent different legends and names to camouflage their anti-Russia drive. The drills are moving increasingly closer to the Russian border; they are held in the Baltic and Black seas, ground exercises are held in Poland and other actions are taken contrary to the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security signed between Russia and NATO in 1997, which sealed the principles of “robust partnership” between them. The key element was NATO’s commitment to refrain from “additional permanent stationing of substantial combat forces” in new member states. This is a good political commitment, just as is the OSCE commitment not to strengthen their security at the expense of neighbours’ security made in 1999 and 2010. The Russia-NATO Founding Act includes a pledge not to deploy “substantial combat forces” in new bloc members. NATO made this “concession” in the context of our argument that it had expanded contrary to the promises made to the Soviet and Russian leaders.

It was a lie. Hoping naively to maintain a partnership with the bloc, we signed the Founding Act, which actually formalised Russia’s acceptance of the bloc’s expansion. In response, NATO pledged not to permanently deploy “substantial combat forces” in new bloc members. Awhile later, we proposed strengthening mutual trust by defining “substantial combat forces” and drafted a concrete legal agreement. The alliance categorically rejected the idea, saying it would provide a definition of “substantial combat forces,” itself, which they had pledged not to deploy permanently and adding that it does not include regular troop rotation. Contrary to its commitment, NATO is continuously deploying substantial forces under the formal pretext of rotation. Until recently, the bloc indulged in a great deal of breast-beating about the absence of any threat to the security of Russia or any other state, because NATO is a defensive alliance that protects the territory of its member state. At least it was clear against whom it planned to protect them in the Soviet and Warsaw Pact era.

The Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union are no more. Since then, NATO has moved its defence lines forward five times. By expanding its zone of responsibility, the “defence alliance” continued to protect itself, even though it was unclear who this was against.

In June 2022, the participants of the NATO summit in Madrid no longer said that NATO is a “defence alliance” protecting the territory of its member states. They openly claimed responsibility for global security, first of all, in the Indo-Pacific region. The have put forth the idea that “the security of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions is indivisible.” In other words, NATO is moving its defence line further east, possibly to the South China Sea. Considering the rhetoric we hear in the EU, the United States, Australia, Canada and Britain, the South China Sea is a region where NATO is ready to whip up tensions just as they did in Ukraine.

We know that China takes a very serious attitude to such provocations, let alone Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait. We understand that NATO’s playing with fire in that region entails risks and threats to Russia. The region is located as closely to Russia as to China.

Russia and China are building up their military cooperation and hold joint exercises, including counterterrorism drills. We recently carried out a joint air patrol mission. For the first time ever, long-range Russian bombers landed at Chinese airfields and Chinese planes touched down in Russia. It is a security measure designed to show our readiness for any turn of events.

It is clear to everybody that US-led NATO is trying to create an explosive situation in the Indo-Pacific Region, just as it did in Europe. They wanted to draw India into their anti-China and anti-Russia alliances, but India refused to join any alliance that was formed as a military-political bloc. New Delhi is only taking part in economic projects offered in the context of Indo-Pacific strategies. After that, Washington decided to create an Anglo-Saxon military-political bloc, AUKUS, with Australia and the UK, and is trying to lure New Zealand, Japan and South Korea into it.

The United States and the EU are dismantling all the principles of OSCE cooperation in Ukraine and are promoting their unilateral approaches. On a larger scale, they are destroying the organisation itself, trying to replace it with all kinds of narrow, non-inclusive platforms like the European Political Community.

The West is acting likewise to erode ASEAN, a comprehensive cooperation platform with such formats as the ASEAN Regional Forum, East Asia Summit and ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting, which have been generally recognised as backbone mechanisms of cooperation in the fields of security, the economy and other areas. They are doing their best to undermine these platforms. Security issues have been removed from the ASEAN agenda. The United States is trying to involve half of the ASEAN nations in its plans, and the other half are keeping away because they are aware of the risks involved.

Washington is taking obviously destructive measures against the comprehensive mechanisms created in Europe and Asia Pacific to address security issues based on equality and a balance of interests. The United States is trying to create irritants and hot spots, hoping that this will not affect it because it is located far away from them. The more crises the Americans create, the more its rivals will weaken each other.

Europe is weakening itself by recklessly following in the US’s footsteps and upholding its Russophobic policy and the use of Ukraine as a weapon in the war against Russia.

Question: Do you believe it is still possible, in the foreseeable future, to agree on the security guarantees that Russia has proposed to the United States and NATO?

Sergey Lavrov: If our Western counterparts realise their mistakes and express their readiness to return to discussing the documents we proposed in December 2021, this will be a positive factor. I doubt that they will find the strength or reason to do this though, but if it happens, we will be ready to return to dialogue.

After our proposals were rejected, the West also took a number of steps that ran counter to the possibility of resuming dialogue. For example, NATO foreign ministers at a meeting in Romania gave assurances that Ukraine would be a member – and this has not changed. At the same time, as Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said, Ukraine must first win the war before it is admitted to the alliance. The irresponsibility of such statements is obvious to anyone who is more or less knowledgeable in politics.

We were ready to discuss security issues in the context of Ukraine and more broadly. The Westerners rejected our proposals in December 2021; the military officials’ meetings and my talks with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in Geneva in January ended in nothing. After the start of the special military operation, we warned that the assertion that Ukraine alone could make the decision on its NATO membership would lead to a dangerous scenario.

In March of this year, the Ukrainians asked for negotiations. After several rounds on March 29 in Istanbul, they finally gave us something on paper. We agreed with the principles of the settlement contained in that document. Among them was ensuring Ukraine’s security through respect for its non-aligned status (that is, its non-accession to NATO), its nuclear-free status (Vladimir Zelensky would no longer be able to declare that abandoning nuclear weapons in 1994 was a mistake); and the provision of collective guarantees not by NATO, but from the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as Germany and Turkey. We agreed to that. In a day or two, the American handlers said to the Ukrainians: “Why are you doing this?” It is clear that the United States expected to wear out the Russian army by using Ukraine as a proxy, as well as have European countries spend the maximum amount of their weapons, so that later, Europe would be buying replacements from Washington, securing revenue for the American military industry and defence corporations. They said the Ukrainians were too early in expressing their readiness to receive security guarantees from the Russians and reach a settlement on this basis.

They keep accusing Russia of seeking negotiations all the time in order to “buy time to raise and send in reinforcements for the special military operation.” This is both ridiculous and frustrating. These people are blatantly lying. We have never sought any negotiations, but we have always said that if someone is interested in negotiating a solution, we are ready to listen. The following proves my point – when in March of this year, the Ukrainians made such a request, we not only met them halfway, but were also ready to agree to the principles that they put forward. The Ukrainian side was not allowed to do this at the time, because the war had not yet brought enough wealth to those who are supervising and directing it – and this is primarily being done by the United States and the British.

Question: Why do you think the OSCE Minsk Group on the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is inactive now? Is there a possibility of resuming its activity?

Sergey Lavrov: The OSCE Minsk Group was created to unite countries with influence in the region, which could send signals to Yerevan and Baku. We agreed that it would be co-chaired by Russia and the United States. At some stage, France, as often happens, said it wanted to join. We decided that Paris would also become the third co-chair.

From then on, for more than a decade, the co-chairs have achieved positive results, meeting with the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan together or separately. One of the landmark joint events took place in Madrid in the late 1990s, where the Madrid Principles were developed, which were later discussed, updated and adjusted by the parties. At the turn of the 2010s, Russia became the leading co-chair. We held about ten trilateral meetings with the leaders of Yerevan and Baku. Representatives of the United States and France attended each of them.

After a 44-day war, the sides reached a ceasefire agreement in September-October 2020 with our mediation. Russia continues to assist Armenia and Azerbaijan in unblocking transport links and economic ties in the region. This should give impetus to the development of other neighbouring states such as Turkey, Iran, and Georgia. We agreed that our country will assist in the delimitation of the border and in negotiating a peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan. All this was the result of summits between the Presidents of Russia, Azerbaijan and the Prime Minister of Armenia.

At the same time, we saw other players making fitful attempts to insert themselves into these processes. We didn’t have any problems with that.

The only change we noted in contacts with Yerevan and Baku was that, after the start of the special military operation, the West, through Washington and Paris, officially announced it would not cooperate with Russia in any formats. This amounted to a termination of the OSCE Minsk Group’s activities. Our Armenian colleagues mention it occasionally. We tell them it is up to the United States and France, which said they would no longer convene the Group, and Azerbaijan, because any mediation efforts are meaningless without it.

Now the French, the Americans and the European Union are trying to compensate for the buried Minsk Group by inserting themselves in the mediation efforts. At the same time, they seek to pick up and appropriate the agreements reached by the parties with Russian participation. For example, a meeting of the border delimitation commission was held in Brussels. The Armenians and Azerbaijanis are polite people, so they come when invited, but how can one discuss any delimitation without maps of the former Soviet republics? And the only such maps are in possession of the Russian General Staff. It’s hard for me to imagine this.

The same holds true for the peace treaty. They went to Prague to attend the European Political Community forum where they signed a document stating that a peace treaty should be based on the borders as prescribed by the UN Charter and the Alma-Ata Declaration of December 21, 1991. At that time, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region was part of the Azerbaijan SSR. Armenia, Azerbaijan, France and the European Council represented by Charles Michel approved this as part of the afore-mentioned document and recognised the Alma-Ata Declaration without reservations. This facilitates further work and resolves the problem with the status of Karabakh.

There is a reason why the Armenian leadership has been talking lately not so much about the status as about the need to ensure the rights of the Armenian population in Karabakh. Baku agrees with this, and is ready to discuss providing guarantees of the same rights as other citizens of Azerbaijan enjoy. No one remembers the OSCE Minsk Group anymore. Occasionally, an Armenian politician will say something, but the Minsk Group was buried by the French and Americans. We had nothing to do with it.

Question: Can you comment on the controversial statements by Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan on the Armenian-Azerbaijani peace treaty and Nagorno-Karabakh? Earlier, he said that Artsakh was Armenia, full stop. He called for the Karabakh people to be brought to the negotiating table between the Armenian and Azerbaijani sides. After the October summit in Prague, he said that Yerevan and Baku could conclude an agreement without mentioning Nagorno-Karabakh. On October 31, right before the summit in Sochi, the Armenian government said they supported the Russian proposals for a peace treaty, which, in their understanding, included a postponement of the decision on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh “until later.” After the meeting in Sochi, demands were made to Moscow to reaffirm the Russian proposals for the normalisation of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, as if Russia had backtracked on something.

Sergey Lavrov: You have clearly detailed the sequence of events. We made proposals in 2012; if those proposals had been adopted, that could have closed this problem once and for all. It was during that time that the idea of postponing a decision on the status of Karabakh “until later” originated. The concept was simple: the Armenians would give up the five Azerbaijani districts around Karabakh, and keep the two districts that link Armenia with Karabakh. The future of those two (no one disputed that they were part of Azerbaijan) was to be determined in conjunction with the decision on the status of Karabakh. This was the first time the idea to postpone the status issue “until later” (for the next generations) was mentioned.

In the autumn 2020, the region was at war. The hostilities were suspended at the preliminary talks stage. Trilateral statements were prepared, and three trilateral summits were held: two in Moscow, and one in Sochi. The participants also talked about the need to launch a political process. There was an understanding that the status of Karabakh could be postponed “until later.” Based on that, Russia proposed its version of the peace treaty, which was sent to the parties in the spring. And it contained that clause. The Azerbaijani side said it was ready to support almost everything, but that the status issue had to be discussed further.

At the end of October 2022, we met in Sochi. We wanted to return to this issue and find out if our partners were ready to act on the basis of a gentleman’s understanding – to resolve the other issues, but leave the status of Karabakh “until later.” President Ilham Aliyev and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan brought to Sochi the same document from Prague, which stated that they wanted to sign a peace treaty guided by the UN Charter and the 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration on the creation of the CIS. That declaration clearly states that the borders between the new states shall be based on the administrative boundaries between the republics of the former Soviet Union, where the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region was explicitly part of the Azerbaijani SSR. And now, after signing that agreement, our Armenian colleagues are asking us to reaffirm the Russian proposals on the status of Karabakh. That is definitely “another book,” not the one about negotiating practices.

Question: Pope Francis has repeatedly proposed mediation, and expressed his readiness to arrange peace talks between Moscow and Kiev. At the same time, the Holy See emphasises the need for long-term solutions and meaningful concessions on both sides. When it comes to concessions, what does this mean for you? What role could Italy, France, and Germany play in this? Or does nothing depend on these European countries anymore?

Sergey Lavrov: Pope Francis has been publicly offering his services for some time. French President Emmanuel Macron has periodically made similar statements. Even German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said he would continue to talk with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Over the past two weeks, Emmanuel Macron repeatedly stated that he was planning to speak with Vladimir Putin. This was rather unexpected, because we had not received any signals through diplomatic channels before these statements were made. The French have a way of making their diplomacy extremely public. We expected him to call if he really intended to. A few days ago, reporters asked him about it again, and he said he was not going to try to contact Vladimir Putin before he went to Washington. From this we conclude that the President of France would discuss not only the weakening of Europe’s competitive advantages there, but also consult on the Ukrainian issue.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has repeatedly said that he was talking with both Vladimir Putin and Vladimir Zelensky. Apart from the Holy See, I have not heard of any initiatives from Italy as a country. My colleague Antonio Tajani (we have not yet met in his current capacity as Foreign Minister) is proposing some ideas for solutions. However, no one is proposing anything specific.

We discussed Ukraine’s proposals at length on March 29; we accepted them, but Kiev was forbidden to implement them. They supposed they needed to further exhaust Russia, and sell more weapons to Europe so that it could give its own weapons to Ukraine.

Pope Francis is calling for talks, but he also recently made a perplexing, very unchristian statement. The head of the Vatican mentioned two ethnic groups in the Russian Federation as a “category” with a tendency to commit atrocities during hostilities. The Russian Foreign Ministry, the Republic of Buryatia and the Chechen Republic responded to this. The Vatican noted that this would not happen again. That it was a misunderstanding. Such things don’t help; they aren’t boosting the influence of the Holy See either.

You asked about possible concessions. When we formulated our proposals in December 2021 (a draft agreement with the United States and an agreement with NATO), we approached those two documents in good faith. We did not insert any poison pills in them. If we had, the first paragraph would have required NATO to disband itself, and the United States to withdraw troops from Europe, starting with tactical nuclear weapons now deployed in Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Turkey. That would be a poison pill.

We tried to be fair. We tried to find a solution that would suit the Americans and NATO, too. We tried to look at the current situation through the eyes of our Western colleagues. This is how those documents came to be. They seemed to contain fair proposals and rely on repeated assurances. In particular, we proposed a return to the 1997 military configuration, when NATO agreed, under the NATO-Russia Founding Act, to refrain from stationing substantial combat forces on the territory of new members.

In Istanbul, the Ukrainians proposed a settlement option. We accepted it, making a fair share of concessions. It was about the situation on the ground at that particular moment. One could continue fantasising about who could propose what. I would like to emphasise that our December 2021 proposals had no poison pills intended to be rejected. In our view, they proposed a balance of interests.

Question: You said in your opening remarks that one of reason for the special military operation in Ukraine was to protect Russian speakers. How can you justify the missile attacks on civilians and infrastructure, which are depriving people of access to water and electricity, including in Kherson, which Russia regards as its own territory?

Sergey Lavrov: Stalingrad was our territory. We whipped the Germans so bad there that they fled the city. The Defence Ministry of Russia and military experts in Russia, the United States and other NATO countries have pointed out that the special military operation has been waged since its inception so as to minimise all possible negative impact on civilians and infrastructure, which is being attacked now. It is no secret that infrastructure is used to maintain the combat capability of the Ukrainian armed forces and nationalist battalions. We are using precision weapons to knock out of service the energy facilities that are important for the operation of the Ukrainian armed forces and for the delivery of a huge number of Western weapons, which are sent to Ukraine to kill Russians.

A European politician has recently said that they should send weapons that can reach targets deep inside the Russian territory. We are aware of this. We are not impressed by words about the West’s interest in a peaceful settlement. The Westerners have stated openly that they not only want Russia to be defeated on the battlefield but to be eliminated as a player. Some people are even holding conferences to discuss how many parts Russia should be divided into and who would control them.

We are targeting the energy facilities that are being used to pump lethal weapons into Ukraine so as to kill Russians. Don’t tell me that the United States and NATO are not involved in this war. They are directly involved in it not only by sending weapons but also by training the Ukrainian military. They are doing this in Britain, Germany, Italy and several other countries. In addition, hundreds of Western instructors (and their number is growing) are working on the ground, training Ukrainians to use the equipment they are sending. There are also very many mercenaries.

Intelligence information, including the Starlink civilian satellites, is being used to identify targets for the Ukrainian military. Information is also provided via other channels. The majority of the targets, which the Ukrainian Nazi battalions and armed forces are attacking, are identified by the Kiev regime’s Western handlers. You should write about this openly. There is enough evidence.

We are using precision weapons to destroy infrastructure used for the military operations of the Ukrainian armed forces.

Social networks, including Telegram, provide the views of experts who rely on evidence and not mere words to explain the difference between our military operation and US actions in Yugoslavia, Iraq and Afghanistan and France’s actions in Libya.

According to a member of the target location centre, who took part in the 1999 campaign in Yugoslavia, it was reported at a meeting a week after the start of the aggression that there were no military targets left apart from the two bridges the Yugoslav military used. They destroyed the bridges and asked what else they could do. It turned out that there was a score of civilian bridges the military did not use. They bombed them, destroying one bridge when a passenger train was running across. No collateral damage, just an attack on a civilian facility. They bombed the television centre and tower in Belgrade because they were used to broadcast propaganda and keep up the combat morale of the Yugoslav army.

The same logic is being used in France now to deny accreditation to RT and Sputnik for an event in the Élysée Palace on instructions from President Macron. The President of France stated that they would be denied entry because they are not media outlets but propaganda feeds. I hope the West will not bomb the RT and Sputnik headquarters and branches in Europe as it bombed the television centre in Yugoslavia.

Take a look at Afghanistan. A large group of people was attacked, and then it turned out that 200 were walking to a wedding. Russia is not a signatory of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Americans are not either, but they are doing their best to instigate the court to open proceedings against those whom the United States views unfavourably.

Several years ago, the ICC decided to investigate the Americans’ operation in Afghanistan and the way they behaved there. There were numerous reports about war crimes committed there by US, British and Australian troops. The Australian government is still waiting for these persons to provide proof of their innocence.

When the ICC was only thinking of opening a case on US war crimes in Afghanistan, Washington unceremoniously announced that it would place the attorneys and judges on the sanctions list. The ICC swept the matter under the carpet.

We are ready to talk about conducting combat operations in modern conditions. But this should be done by professionals. It is no good making unsubstantiated statements for political gain, putting all the blame on somebody and forgetting about very serious situations which everybody ignored, including media outlets that are working or covering developments in Russia.

There was civil unrest on Maidan in 2013 and a coup in 2014, which took place contrary to the agreement on settling the problem reached with the EU’s mediation. We warned that those who had come to power and declared that their goal was to expel Russians from Crimea and prohibit the Russian language posed a real threat and should be told to back off. Nobody as much as lifted a finger. And then a war began, and the Minsk agreements were signed with EU guarantees, but nobody did anything again. Neither Poroshenko nor Zelensky implemented them. Instead, they said that abandoning nuclear weapons was a mistake, that they would return Crimea, that they had signed the Minsk agreements to gain time, and that they would be given weapons and would solve the problem with military force.

We appealed to Berlin, Paris and Washington to reason with the Kiev regime, which they controlled, and to force the brazen racists to back off. They did not respond. We tried to get their attention for several years. There is a lot of noise in the media now about how they supposedly didn’t know what was going on in Ukraine after the Minsk agreements and didn’t hear our appeals to reason.

Compare the current hysteria in the Western political community which the media try to enforce with what was going on when the United States bombed Iraq. The Americans did not complain for years that Iraq prohibited the English language or Hollywood films; they just showed a vial of white powder as proof that Iraq was making biological weapons. And they bombed out a country that did not pose a threat to it and was not located directly on its border but 10,000 miles away. They did it because they think they are allowed to do it. It is the cardinal rule of their world order. As for Russia, we tried to protect our legitimate interests in accordance with international law and not according to American rules.

What did Libya do wrong? Its only sin was that a European leader or some of Libya’s neighbours did not like Muammar Gaddafi. The country was well off, just as Iraq. Despite their strict autocratic regimes, the economic and social situation was much better during their time. There weren’t millions of refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya in Europe. Did anybody stop to think about that then? When Kirkuk in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria were razed to the ground, dozens of dead bodies lay there for weeks on end. All the survivors fled.

It looks as if the Western propaganda only rings the alarm bells when those who have pledged loyalty to the West suffer. The West uses them as instruments for attaining its geopolitical and military goals. In this case, it is the Ukrainians.

The West has killed infinitely more Arabs in Iraq, Libya and Syria or Afghans in Afghanistan. I don’t remember the West showing as much concern for their civilian populations. Does this mean that they are regarded as subhuman in the West, and that Ukrainians, who claim to be the descendants of ancient Romans, deserve to be given special protection by Western institutes and agencies?

I regret and grieve any loss of life, especially as the result of a military conflict and damage to civilian infrastructure. However, we must address this problem honestly and without double standards.

Western political analysts and warfare experts have a great deal of information, statistics and arguments at their disposal. They know how wars are waged, and when wars are waged recklessly and without any restraints, and when the armed forces involved try to observe as many restraints as possible to minimise damage to civilians and civilian infrastructure.

Question: Russia and the US reached their main targets on arms control under the START-3 Treaty in 2018. Five years have passed since then. Isn’t it time to take more ambitious steps on cuts in strategic offensive arms? What steps does Russia expect from the US, if any?

Sergey Lavrov: This question is not for me. It was not us that took a pause in the talks on potential new agreements to further limit strategic offensive arms – post-START. These talks took place – the first round in July, and the second in September 2021. Our positions were opposite. The Americans wanted to focus on our new weapons announced in 2018, primarily five supersonic systems. We did not fully reject this. We agreed that two of these systems – Sarmat and Avangard – could be covered by the 2010 START-3. Other systems did not fit in with the treaty’s parameters. We expressed a willingness to discuss further steps on arms control, affecting our new systems with the understanding that Russia also wanted the Americans to take some steps towards rapprochement to our positions.

At the September meeting in 2021, the negotiators agreed that two expert groups would be in charge of further efforts. One was supposed to determine what types of arms were strategic and could be used for strategic purposes. This was a matter of principle for us. We suggested a systematic approach to the subject of a future treaty. Including some new weapons in the treaty was not enough. First, it is necessary to analyse which of the weapons they and we have that are actually strategic in nature, regardless of whether they are nuclear or non-nuclear. The US’s Prompt Global Strike system is non-nuclear but is more efficient in reaching military targets. It is necessary to maintain a balance if new arms come into use. We agreed that the experts would sit down and honestly work on deriving what Vladimir Putin called “a security equation.”

In 2021, COVID-19 did not prevent us from holding two useful meetings. However, after September, the Americans did not wish to continue the talks. This was long before the start of the special military operation. It is hard to say what the reason was. To all intents and purposes, the responsibility of Russia and the US as the world’s largest nuclear powers (at this time) has not disappeared. In June 2021, the presidents made a joint statement to the effect that a nuclear war cannot be won and must not be unleashed for that reason. A similar statement by the five nuclear powers also exists. As I have said more than once, we were ready to go further and say not only that a nuclear war must not be unleashed, but also that any war between nuclear states was unacceptable. Even if a country starts a conflict with conventional arms, there remains the enormous risk of it escalating into a nuclear conflict. This is why we are watching with concern the rhetoric of the West that accuses Russia of preparing provocations with WMDs. In the meantime, the West itself, including the three nuclear powers – the US, UK and France – is doing all it can to build up its almost direct participation in the war that it is waging against Russia with Ukrainian hands. This is a dangerous trend.

Question: European security also includes energy security. Europe is now debating the price cap for Russian oil. Russia’s stance is well known. If we assume that the price cap will be high enough (the proposals vary, 30, or 60 dollars per barrel are mentioned). If the price is at the market level, what will happen in that case? Will Russia refuse to supply energy resources to the countries that support this mechanism? How big a role does the price play?

Sergey Lavrov: Our approach has been spelled out by President of Russia Vladimir Putin and Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak who oversees energy. Once again: we will not supply oil to the countries that conform with dictators. Dictating prices to the market is an extremely unusual turn for those who have defended free markets, fair competition, the inviolability of private property, and the presumption of innocence for decades. Among other things, it sends a strong and enduring signal to all states, calling them to reflect on how to avoid using the tools imposed by the West within its globalisation system.

Russia is already “undesirable.” China is becoming the target of sanctions and is now forbidden to sell or buy goods that Americans want to use to strengthen their competitive advantages. Anyone could be next. There is no doubt that the seeds of a long process of reformatting global mechanisms have now been sown. Considering the schemes the European Union is resorting to, there is no confidence in the dollar, and the euro can be used in fraudulent schemes. Head of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen tried to justify the laws that need to be adopted in order to steal money from the Russian state and citizens. The European Union is exhibiting a tendency to return to its colonial ways and live at the expense of others. America is sponging off Europe, so Europe needs to live off someone. They are casting about for a target, and considering us.

I am sure that we will not abandon this principle. This is not about higher oil revenues today; it is about the need to start building a system independent of these neocolonial methods. We are working on this with our BRICS colleagues (and with a dozen countries wishing to closely cooperate with BRICS), the SCO, the EAEU, and in bilateral relations with China, Iran, India and other countries.

We do not care where exactly they cap the price. We will reach agreements with our partners directly. They will not cautiously toe anyone’s line or give any guarantees to those who illegally draws those lines. When we negotiate with China, India, Türkiye or other major buyers, we always observe a balance of interests in terms of the timing, volume and price. The terms should be agreed on a reciprocal basis between the producer and the consumer, and not as punishment.

Question: In your opening remarks and responses, you spoke in detail about Russia’s position on European security. We heard about this a year ago. What do you think, as the Russian Foreign Minister, about the likelihood of a meeting next year between the presidents – Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden – or a meeting with you and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken? Are any top-level meetings possible at all in the near future?

Sergey Lavrov: Our current assessments on the state of European security nearly coincide with what we said in 2020 and 2021. This only emphasises the consistency of our position, the long-term crises in the European security system and the West’s reluctance to listen what we are saying.

There is a principle according to which every state must think about its own security itself if collective security does not work out. The threat to Russia that is being created by the US and its allies from Ukraine, is real, existential. A compatriot of our Polish neighbours, Zbigniew Brzezinski, said in 1994 that everything must be done to break Ukraine away from Russia because Russia and Ukraine are an empire, whereas without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire and becomes a regional player. In 1994, we had very good relations with the US but even then nobody wanted Russia to be independent, even to a limited extent. This is where this was rooted and accumulated.

I have cited the example of Iraq. They said Iraq had WMDs one day, and the next morning they flew there and started bombing. But they did not find anything. Later Tony Blair regretted this as a mistake – this can happen to anyone. Hundreds of thousands of people were buried. Meanwhile, the country lived a normal life and did not have any big socio-economic problems but it was destroyed. Now it is being rebuilt from fragments, just like Libya. But all this happened ten thousand miles away, across the ocean. They are allowed to do anything. They claim these are different things because they are supposedly fighting for democracy. This is why they can kill more than a million people, and this is what they did. Where is democracy in Afghanistan? In Iraq? In Libya? Terrorism is now rampant everywhere. There are millions of refugees in Europe, but this could have been avoided.

It is not without a reason that we had to act in Ukraine. It is not that we did not like Vladimir Zelensky because he stopped playing in the Club of the Funny and Inventive or because he quit funding his Kvartal-95 Studio. This is not why we “went to war” with Ukraine. We warned them for many years but nothing changed.

To begin with, we want to understand who can offer us something and what it is. You asked about meetings between Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden. We (including the Russian President) have said many times that we never avoid talking. When German Chancellor Olaf Scholz wanted to come we said “Welcome.” When Emmanuel Macron wanted to come, we also said “Welcome.” Do you want to call us? Anyone who asks about calling will have this opportunity without any time limit. However, so far we have not heard any meaningful ideas.

Our American colleagues suggested holding a meeting between Bill Burns and Sergey Naryshkin. We agreed. Importantly, the Americans told us many times that this must be a strictly confidential channel. We cannot mention it so that nobody will know anything about it. This must be a serious channel immune to any external propaganda intrigues. We agreed. However, their arrival in Ankara was followed by an instant leak. I do not know from where – the White House or the Department of State. Now Charge d’Affaires at the US Embassy in Moscow Elizabeth Rood said they would continue maintaining this confidential channel. Sergey Naryshkin also had to speak and said what issues they discussed – nuclear security, strategic stability, the Kiev regime and the situation in Ukraine in general.

The Americans and others are saying that they will not discuss Ukraine without Ukraine. First, NATO is discussing Ukraine without Ukraine, Ukrainian delegates are not invited there. Second, it is abundantly clear to everyone that today it is impossible to discuss strategic stability while ignoring everything that is happening in Ukraine today. The goal is not to save Ukrainian democracy but to defeat Russia on the battlefield and even to destroy it. We are told that Ukraine can only be discussed with Ukrainians present and only when they want to do so. So, in the meantime, is a discussion on nuclear arms and strategic stability being suggested? This is a naïve approach, to put it mildly.

If there are proposals from the US president and other members of his administration, we never avoid talking. Mr Blinken called us once some time ago. But he was worried about American citizens that were sentenced here and serving a prison term. That said, he must know that to discuss this particular issue, the presidents agreed in Geneva in June 2021 to create a completely different channel, a channel between secret services. It is working, and I hope some results will be reached. We have had no contact with Antony Blinken on general political issues. As I understand it, there is a “division of labour.” Jake Sullivan’s team wants to do something. The Department of State wants to do something else. We do not delve into the functioning of the US bureaucratic machine. Such decisions are up to the president and other leaders.

Question: You mentioned the NATO meeting that ended the day before yesterday in Romania. Many analysts recalled that it was in Bucharest where then US President, George Bush Jr, said that Georgia and Ukraine could join NATO for the first time.

I would like to ask you to comment not so much on this as on the statement by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. He spoke about the need to expand NATO presence from the Black to the Baltic seas. What does this mean for Russia and how will it respond?

Sergey Lavrov: As for this pronouncement, he made it in parallel with a statement by Jens Stoltenberg who said that to reach peace in Ukraine, it is necessary to continue pumping the Kiev regime with arms. A schizophrenic approach. If you want peace, prepare for war. The only difference is that here, it is not “prepare for war” but fight to the very end. This is the logic.

Blinken’s words show who is setting the tune in NATO today. The three seas idea – to build a cordon against Russia from the three seas (from the Black to the Baltic seas) initially came from the Poles. It was enthusiastically supported by the Baltic states and has been promoted for several years as a concept for “reviving” Polish glory. They started promoting this before the special military operation and intensified the effort after it started. The fact that Blinken has now picked this logic is very indicative. It means that the Americans now rely on Poland and the Baltic states in developing NATO. These countries are the most Russophobic and racist. Countries like Germany and France are being relegated to the background. I have already commented on the French president’s “strategic autonomy concept” that is obviously at variance with the American thoughts. The Americans believe the European Union does not need any “strategic autonomy.” They will decide themselves how the EU will ensure its security according to American patterns.

Former Chancellor Angela Merkel lamented in a recent interview that after the summit between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin in Geneva in June 2021, she suggested, with Emmanuel Macron, holding an EU-Russia summit but was blocked from doing this. Who can stop German and French politicians from meeting with whomever they want in normal times? This was done by the Poles and the Balts that are building this cordon and promoting the three seas concept. This is a very important sign.

Incidentally, a few words about the EU’s influence. In February 2014, the EU guaranteed a settlement between Viktor Yanukovych and the opposition. A relevant document was signed. It starts with the words “to establish a government of national accord” and to “hold early elections.” Vladimir Putin said this many times. It would have worked if they had held these early elections, as was agreed upon. Yanukovych would never have won them. The same opposition members who staged the state coup the next morning would have come to power. It is unclear why they were in such a rush. They could have abided by the document that was guaranteed by Germany, France and Poland. There would have been no Crimean referendum, nor the subsequent events. Nobody would have rebelled against these people because the agreement on holding elections would have been valid.

This did not happen without a US “contribution,” either. Everything we are talking about happened in February 2014. Maidan was over; the agreement on a settlement was signed and guaranteed by the EU countries. A month prior to this, Victoria Nuland, who was in charge of the post-Soviet space at the time, was coordinating the composition of a new government by telephone with the US Ambassador in Ukraine, apparently, expecting this coup to happen. She mentioned several names but the Ambassador told her that the EU did not like one candidate. Do you remember what she said about the EU? She used a four-letter word.

The same attitude has prevailed towards the EU ever since. At first, the EU’s guarantees and agreements between Yanukovych and the opposition were trampled underfoot. Then the same lot befell the guarantees given by the EU – Germany and France – to the Minsk agreements that envisaged a direct dialogue between Kiev, Donetsk and Lugansk and the preservation of the Russian language. In 2019, French and German officials again invited new President Vladimir Zelensky to Paris. This was a meeting in the Normandy format. He again promised to come to terms with Donetsk and Lugansk on their special status and to seal it permanently, but he did not do anything, either. The EU was repeatedly whipped for its mediation.

In 2018, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Frederica Mogherini said that when the EU is in the region (meaning in the Balkans) there is no room for anyone else. She implied that the Russians had nothing to offer in the Balkans and that their contacts with Serbia and other Balkan countries must be discontinued.