The struggle for & against one-world domination

Turning points in world history are mostly triggered by conflict of interests among old and new powers with their relevant circles of society and being confronted by economic upheavals.

Industrialization and simultaneous colonization provided Great Britain with the foundations to compete with the Russian Tsarist Empire – the largest land power in Eurasia – as a world power in the 19th century:

Source: The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, a balance of power in Europe was able to safeguard the given order for over a century until 1914:

The continental powers of Central Europe and Asia followed industrialization, as demonstrated by Great Britain, but with a time lag behind. Globalization and colonial policy were largely dominated by the maritime powers of Western Europe. This development caused the globalists to shift their centres of global control from the former Byzantium, Venice, Genoa, Switzerland and Netherlands towards the West – i.e. Great Britain and later also USA.

The unifying signature of “global” heraldry can be seen in insignia:

Source: Cplakidas, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: UnknownVector:User:Marc MongenetCredits:User:-xfi-User:Zscout370, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Genoa.svg

Source: traditional Vector: Nicholas Shanks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Greentubing, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Original code by Stefan-Xp with modifications to ratio by Yaddah., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

From 1190, English ships in the Mediterranean used the Genoese flag being placed under the protection of the Genoese fleet. The English king had to pay an annual tribute to Genoa for that. Later the flag became that of England and remained so until today.

Towards the end of the 19th century it became apparent that:

- Great Britain in its given shape would not be able to maintain its monopoly position against rapidly growing continental powers.

- the multipolar world order at the turn of the century in 1900 intertwined with world trade, stood at the opposing end to the concepts of the One-World- Hegemony driven by the globalists.

Against this background, transnational circles from UK agreed to have lifted the United States the to a centre of global governance as conceptual-state in alliance with Great Britain. The agreement was reached informally at the supranational level and has been only communicated to the outside world under the hazy term of “Special Relationship.”

A dress rehearsal of the new combination had been made possible in concerted action at the turn of the century via the British Second Boer War (1899 – 1902) and the bloody colonization of the Philippines by the United States via the American-Philippine War (1899 – 1902). After the leap over the Pacific to the Philippines, the USA reached-out over the Atlantic in the course of the 1st World War (1914 – 1918) for dismantling Middle Europe: For this the United States had to declare their (world) war to the II German Empire on April 6, 1917 and Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917. The destruction of Middle Europe was the necessary step in the ongoing construction of Atlantic world domination.

Thus, representatives of the globalists had repositioned the concept-state USA as a global control-centre on the ruins of the British Empire in 1917. World War I, however, had put an end to the UK holding the world currency: By 1919 the US-Dollar took over from the British Pound Sterling as the new world currency in place.

Phenomena of Transnational Global Domination

The disempowerment of nation-states and transformation into protectorates, project – as well as souvenir states has become the preconditions of monopolar global domination and has become visible as phenomena:

The miraculous increase of nation states after 1918.

At the turn of the century 1900, there were 54 sovereign states, including nine great powers by representing basically a multipolar world order.

The United Nations had 51 founding members in 1945. But only a short time later, the United Nations had grown to 193 states. Mass media and political representatives tirelessly portrayed them as “sovereign” and “equal” to each other only.

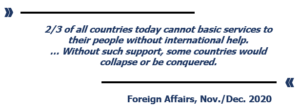

But what do Atlantic analysts in small circles say about this?

Such insights of Atlantic political scientists make it clear, that the miraculous increase of nation states after World War I had often produced only designer states and protectorates. Thus, it was not multipolar diversity that shaped the new world order, but rather monopolar forces operating in the background.

Such insights of Atlantic political scientists make it clear, that the miraculous increase of nation states after World War I had often produced only designer states and protectorates. Thus, it was not multipolar diversity that shaped the new world order, but rather monopolar forces operating in the background.

The goal of the globalists has been, in the first step, to eliminate all multi-ethnic states from the scene: At the time of World War I, these were the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and, last but not least, the most important of the three – the multi-ethnic state of Russia. Russia unites 180 ethnic groups under its federation and commands over size of lands and resources which allow absolute sovereignty and autarky. But the break-up of Russia was not succeeding until today: Not in World War I – not in World War II – not in the 90’s despite «reform oligarchs» and not even today: With NATO and the “combined West” in full wartime action.

The dismantling of the multi-ethnic states serves the purpose to turn the fragments into fake-sovereign protectorates or vassal states, like for example the Baltic States. At the time of the founding of Lithuania in 1991, there were 3,706 million people living in Lithuania – in 2018, there were only 2,721 million left. Today, the remaining populations of the Baltic states have been “looked after” by the US embassies. This also explains why, for example, Lithuania risks confrontation with China over the Taiwan issue: Micro-states are sometimes sent as test trails ahead.

The gap between rich and poor is widening.

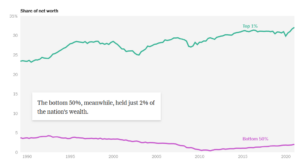

A look at the U.S. wealth distribution from 1990 to 2020 makes it clear, that:

- the richest 1% were able to increase their share to 32% thanks to CoV.

- the bottom 50%, however, were left with a wealth share of only 2%.

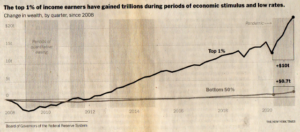

The increase in wealth in the USA since 2008 thanks to CoV shows, that the:

Source: NYT Screen Shot

- Top 1% increased their wealth by 10 trillion USD during CoV

- Bottom 50% could only increase their wealth by a marginal 0.7 trillion USD

The statistics show: The national emergency decrees, directed against majorities, favoured and triggered a drastic redistribution of wealth from the bottom to the top.

Conflict between global, hegemonic & national power

The ongoing turn of an era will result in a new world order, which will be decided by a political – and military struggle between the following three groups of actors:

The Globalists

In 2009, a study by ETH Zurich provided evidence that, contrary to popular belief, global politics can be scientifically proven. It is determined and led by an extreme small group of people.

The scientists of the ETH from Zurich summarized, as follows:

The researchers examined 37 million companies from which they filtered out 43,060 transnational corporations (TCNs). A core of 1,318 companies control 20% of all revenues, but through shareholdings control another 60% of all global revenues: Less than 2% of all transnational corporations control 80% of revenues.

This has become extended by a collusion of a few dozen financial groups in the style of a closed society. The ETH report shows that in contrast to the extreme corporate collusion at the global level, the exact opposite is only true for local companies at the European level.

This development challenges not only economic competition, but also the sovereignty of nation states. Because, unlike entrepreneurs of national medium-sized companies, which have been conditioned not to get involved in political events in a sufficiently comprehensive way, globalists, in addition to controlling their financial & economic monopolies, see no problem in acting-out politically and making their political will clear to the political establishment at the state level and, if necessary, imposing it by force.

For example, during the CoV pandemic, the manifold «experts of science» showed how to keep national governments incapable of acting and how to turn them into command receivers of transnational interest groups in the twinkling of an eye.

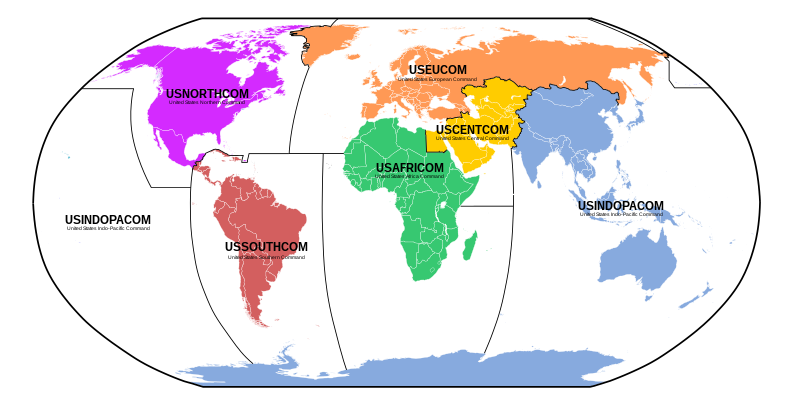

U.S. country elites and hegemonic forces.

As mentioned, U.S. country elites had been selected for their future role as world policemen in the late 19th century as part of the «Project USA». The plan has been realized and given the executors invaluable advantages, such as being allowed to notoriously plunder the world, as has been accurately reflected by the chronic U.S. current account deficits over so many, if not all the decades.

The American establishment quickly became accustomed to their new lifestyle. A major problem arose only after the globalists decided at the end of the last century to move the Atlantic control centre to the Far East. It means that many of the previously needed local servants on the ground in the West would no longer be needed in the future any more.

The U.S. country elites seem unwilling to relinquish their privileged position as world policemen and modern feudal lords without resistance. They prefer to stick to their hegemonic position by means of an over-aggressive war policy – it could even be called a World War 3.

The Secretary of the Security Council of Russia, Nikolai Patrushev put it this way:

The first phase in the war against Russia by Atlantic hawks foresaw to crush Russia by a coup in Russia and a “victory” of the Ukrainian military in parallel(!) enabling to lead the main strike against China subsequently. The options of the US war party do not exclude a limited nuclear strike against Russia as well as against China in that context.

Globalists, however, are not willing to take such deadly risks and decided – regardless of their own plans – to act against such high-risk policy of the US hawks in the short term.

The 85% rest as representatives of a multipolar world order

They encompass the great powers Russia, China and India with all the other states that do not belong to the West – a total of 6.6 billion inhabitants world-wide.

Some of these states had become victims of colonial history. In the new millennium, this has made them to stand-up against the so-called “West” and have created a new, more just world order at the appropriate moment of time.

In the sleaze of the revolving doors of Atlantic shadow orgs

Hegemonic concepts are developed at the transnational level, but must be handed down to non-state actors and organizations for implementation. The realization is supposed to be inconspicuous to the outside in order to manipulate populations as smoothly as possible. It is sufficient thereby to occupy only those areas of the control, which are necessary for the realization of appropriate concepts, like mainly:

- Educational institutions, cartel media incl. the cultural sector

- Economic policy and legislature

- Foreign and monetary policy

Since the 19th century, transnational elites have made use of so-called «think tanks» for this purpose to further advance the development of Atlantic colonial & monopoly policies on the operational level: As for example initially with the help of the Fabian Society (1884) or after WW1 via Chatham House (1920). The newly invented “world policeman USA” has been supported by the Council on Foreign Relations (1921) and other related constructs.

The Fabian Society in the course of time: From wolf in sheep’s clothing to new logo|Source: Fabian Society, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Fabian Society in the course of time: From wolf in sheep’s clothing to new logo|Source: Fabian Society, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The overall system is decisive – not just a single component | Source: CC/PFR

Squaring the Circle or that of Global Dominance

The end of the Cold War in 1990, which triggered the phase of “open borders” similar to the times before 1914, caused the founding of new think tanks to skyrocket: It is estimated that today there are more than 8,000 such constructs worldwide existing, which claim to analyse issues for governmental as well as supranational clients or had been assigned to participate in the implementation of relevant concepts.

About 50% of all think tanks are located in the USA and Europe and are instrumentalized by national elites as well as globalists. About 2,000 of them are domiciled in the USA: They operate branches in Europe and Asia with their objectives to foster the protectorates. Outsiders often tend to perceive think tanks as a strange or even charitable type of association and get mislead.

Think tanks are used by supranational actors on a project-by-project basis to implement global concepts and disseminate the required narratives. This also includes prescribing the foreign policy for the protectorates and get those synchronized with that of the hegemon respectively.

In principle, think tanks are «shadow organisation» of supranational power. Particularly leading clans at the control level oversee a large number of think tanks, collusion with respect to concerted and covert actions has already been organizationally provided for in place.

For example, the «Peterson Institute for International Economics» was founded only on the recommendations of the presidents of GMF and CFR: It’s that simple!

Leading think tank staff sometimes work on different platforms at the same time. In the USA, it has become custom that politicians who have turned unemployed after the change of administration get temporarily absorbed by think tanks according to the so-called “revolving-door-principle”: Until their next mission. This is how politicians and political pawns are controlled in the land of unlimited opportunities.

There are also so-called “phantom think tanks” that give a distorted impression to the public and hide their true missions behind a facade. A misleading name, for example, may create false associations in the external perception by third parties, but as had been designed for.

The German Marshall Fund can be cited as a case study and shining example:

- Contrary to what the “German” in the name might suggest, that organization was not founded in Germany, but maintains its headquarters in Washington DC with only branches in Berlin, Brussels, Ankara, Belgrade, Bucharest, Paris and Warsaw. Among the foundation’s goals is mentioned to “deepen relations” between EU-states and the United States. Appropriate cultivation of young prospective politicians has been carried out, as done for Annalena Baerbock or Cem Özdemir. In 2021, GFM had assets of USD 211 million and generated revenues of USD 67 million. The European Commission, the German Federal Foreign Office, Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs each donated more than $1 million to GMF in 2022.

- Contrary to what the “German” in the name suggests, the “GMF” has nothing to do with the “Marshall Fund”, but was established as a gift from the German taxpayer a full 25 years after the real Marshall Plan was launched in 1972: With DEM 150 million, which was passed via a separate law by the Bundestag of the four parties in 1972. Obviously, this amount was too little for the recipients, so Helmut Kohl increased the donation of the German taxpayers by another 100 million DM in 1986: This financing procedure reminds of past tribute payments, but in a very modern guise.

- On its website, GMF, in cooperation with NewsGuard, declares alleged misinformation to classify as either “false content producers” or “manipulators” and to finally have them publicly denounced. GMF pretends to know that with regard to the last U.S. presidential election, as well as on the spread of CoV, «false and manipulative content» had been in existence, which allows GMF to qualify free expressions of opinion, whenever other opinions do not fit.

- In this way, alternative media became vilified by GMF whereas the narrative of censorship is insidiously publicized in the public sphere via the back door.

GMF in the footsteps of the Trilateral Commission

Similar to the Trilateral Commission, which was established in July 1973 at the suggestion of Zbigniew Brzeziński and David Rockefeller to organize a united front against the UdSSR, the GMF’s current agenda seems fully focused on raising a «transatlantic front» against China. Preparations for this target seem well underway, as two hearings before the U.S. Senate Committee by two senior transatlantic fellows of the “German Marshall Fund of the U.S.” make very clear:

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation

Hearing “Aligning transatlantic approaches on China”

June 7th 2023 Written Testimony

Andrew Small, Senior Transatlantic Fellow,

the German Marshall Fund of the United States

Andrew Small, Senior Transatlantic Fellow,

the German Marshall Fund of the United States

…

Over the last few years, Europe and the United States have engaged in the most significant overhaul of their policies towards the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since the opening of diplomatic relations. While the United States has moved further and faster in this process than Europe, the nature of the two sides’ economic, political and strategic concerns about the PRC, and the analysis of how best to respond, has been highly convergent.

This is reflected in the quality of transatlantic exchanges on China. Where it was once contentious even to address China-related concerns openly between Europe and the United States, collective efforts to do so are now embedded across all dimensions of the transatlantic relationship, from summits to working-level coordination, NATO to the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC). The urgency gap that existed between the two sides is starting to close.

…

European capitals are now converging on a new set of policy objectives with China for the first time since 2019, when the EU’s framework of treating China as a “partner, competitor and systemic rival“ was first laid out. European Commission President Von der Leyen’s March 2023 speech on how Europe should deal with a China that is “more repressive at home and more assertive abroad” was an indication of the direction of flow. EU member states have again given the Commission space to be bolder and clearer than some of them are willing to be themselves.

…

China’s pushback

…

At the same time, Beijing has essentially decided to accept some level of collateral damage to its standing in Europe as the price for deepening and elevating its ties with Moscow at a time of war. In a previous phase of Chinese foreign policy, Xi would neither have agreed to the “no limits” joint statement with Putin in the crucial weeks before the Russian invasion nor embarked on a full-scale state visit to Moscow at such a contentious juncture a year later. But in the wider struggle that the PRC understands itself to be engaged in with the United States, Xi sees the partnership with Russia – even a weakened Russia – offering greater strategic benefits than any other relationship.

…

Taiwan

Where the Sino-Russian relationship and the de-risking question are at the top of Europe’s China debates, the Taiwan question occupies a more delicate and complicated role. There is now clearer awareness of the risks and the stakes for Europe, with the economic shock alone of any cross-Strait conflict dwarfing that of Russia’s invasion. The breadth of the sanctions imposed on Moscow has also turned Europe into a part-player in Taiwan-related deterrence efforts that it was not eighteen months ago. China is well aware that the sanctions-coalition is one that could be replicated for Taiwan contingencies, and saw Europe going far further with Russia than it had anticipated, with Chinese officials scrambling – for instance – to figure out the implications of the central banking asset freeze.

Yet while there is now European willingness to warn China about the need for stability; to make clear that Europe also has a stake in cross-Strait security; and to find creative ways to expand relations with Taiwan – consistent with a One China policy – there is still caution about detailed transatlantic contingency planning for any sanctions measures. This is not just out of neuralgic anxiety about antagonizing Beijing: there is also a concern among European policymakers that any pre-emptively agreed lowest common- denominator measures may do more to underwhelm than deter. For now, the PRC has to take into account Europe’s demonstrated capacity to surprise on the upside with sanctions. And Beijing is well aware that while Europeans may be cautious about advance signalling, and may not be willing to act decisively for the sake of Taiwan alone, the US frontline position in any conflict scenario will ensure that Europe feels obliged to do so regardless.

…

The transatlantic action agenda – progress and prospects

As the recent G7 summit in Hiroshima highlighted, United States and Europe, and their wider network of partners and allies in the Indo-Pacific, are now more closely aligned in substance. Where prior summits still saw differentiating language on China from European leaders, reflecting their concerns about “bloc politics” and “confrontation“, this looked closest to a real consensus rather than a paper one. The issues at stake have high stakes for the future international security order and major economic interests at home, and will be subjected to fierce intra-European and transatlantic debate. But depicting this as “division” obviates the fact that agreements on consequential areas of policy continue to be reached nonetheless. It is not an analytical mistake that Beijing tends to make.

For now, the fastest-moving areas of cooperation have been on the defensive side. Europe’s progress on agreeing an economic security strategy offers the prospect that it will move out of reactive mode on issues ranging from export controls to outbound investment screening. But even if the United States remains the pace-setter, there is now a suite of different areas in which the two sides are in synch, and can be expected to line up their approaches in the coming years. Despite this, it will remain important for the United States to be vigilant across areas of security where gaps and deficiencies are already appearing, such as the lagging of certain European countries on rollout of secure 5G networks, and the expansive openings for Chinese actors in other areas of Europe’s digital infrastructure.

…

Conclusion

The United States and Europe have reached a far deeper level of coordination on China than looked plausible a few years earlier. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might have been expected to consume the two sides’ political focus; it has instead led to an even greater awareness of how closely the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres are now interconnected. The coalition that the United States needs to build to address the shared challenges posed by China spans multiple domains and geographies. Europe will remain a vital part of it in the years to come.

***

Testimony for the Senate Foreign Relations

Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation

June 7th 2023

Hearing: “Aligning transatlantic approaches on China”

Noah Barkin

Senior Advisor, China Practice, Rhodium Group

Visiting Senior Fellow, Indo-Pacific Program, German Marshall Fund of the United States

Chair Shaheen, Ranking Member Ricketts, distinguished members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to talk to you today about transatlantic cooperation on China.

Europe’s relationship with China has been worsening for more than half a decade, mirroring the decline in relations between Washington and Beijing.

In past years, European concerns centred around issues of economic competitiveness and market access. But they have since broadened to encompass worries tied to human rights, economic coercion, strategic dependencies, disinformation, and security.

Europe entered a new phase in its relationship with China following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The “no limits” partnership sealed between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in the weeks before the war began and China’s subsequent refusal to condemn Russia’s aggression, are cementing the view of China as a competitor and systemic rival. Importantly, the war has also increased awareness, both in European governments and corporate boardrooms, about the risks of a conflict over Taiwan.

Today, there is an intense debate underway in major European capitals about reducing economic dependencies on China. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen delivered an important speech on March 30th in which she argued for a “de-risking” of the Europe’s relationship with China. Over the coming months, Europe will begin the process of defining what de-risking means in practice.

The hardening of Europe’s line can obscure differences that exist between the 27 EU member states, and in some cases, within individual European governments. On the hawkish end of the spectrum are a group of eastern European countries led by Lithuania, which promote a values-based foreign policy. At the dovish extreme is a country like Hungary. The largest EU states, including Germany and France, fall somewhere in between.

As we saw on President Emmanuel Macron’s recent trip to China, France stands out for its support of European strategic autonomy – code for an independent Europe that is not overly reliant on China or the United States. Germany stands out for having what is by far the closest economic relationship with China of any European country. According to new figures from Rhodium Group, German firms accounted for 84 percent of total EU foreign direct investment in China last year.

Germany is also the country in Europe where the debate over relations with China is the most intense. Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition is divided over how far and fast to go in recalibrating ties with China. Still, it is fair to say that the “win-win” economic narrative that fuelled close ties between Berlin and Beijing in recent decades is increasingly being eroded by conditions on the ground in China and competition from Chinese firms in core German industries.

I’d like to conclude with a few observations about transatlantic cooperation on China.

First, I believe we have seen a great deal of convergence between the US and Europe over the past two years on the language that is being used to define the challenges posed by China. In recent months, we’ve seen senior officials on both sides of the Atlantic embrace the term de-risking. And we’ve seen officials distance themselves from the idea of a full-blown economic decoupling from China.

Second, this alignment is more than just rhetorical. There is a growing transatlantic consensus on the need to reduce dependencies on China, diversify to other markets, and improve the resilience of supply chains.

Third, the US and EU have created a series of structured dialogues on China related challenges in recent years. The US-EU Trade and Technology Council held its fourth ministerial meeting in Sweden last week. China also features increasingly in discussions within NATO and the G7.

Fourth, as I mentioned earlier, the war in Ukraine has pushed the US and Europe closer together and focused minds in Europe on the risks of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait.

That said, it is wrong to expect perfect alignment between the US and Europe on China. The US is an incumbent superpower. It plays a vital security role in the Indo-Pacific. And it is not a collection of countries with different interests like the EU. As a result, it sees China through a different prism than Europe does. And its response reflects this.

There is no appetite in European capitals for containing or isolating China, and there are concerns in some capitals about what is perceived as an overly confrontational approach from some politicians in Washington, particularly on the issue of Taiwan.

There is a consensus in Europe that despite the growing strains – but also because of these strains – one must continue to engage robustly with Beijing. As a result, we have seen a flurry of visits by European leaders since China ended its strict zero-COVID policies at the end of last year.

While there is a nascent push in Europe to reduce dependencies on China, the appetite for paying an economic price in the name of national security is not as developed as it is in the US or in a country like Japan. The threat perception is evolving in Europe, but more gradually. As we’ve seen on Ukraine, however, Europe is capable of major shifts in policy in times of crisis.

I am convinced that building transatlantic convergence on China, and limiting the risks of divergence, depends on robust engagement between the US and EU on the trade, technology and security issues that are at the heart of the challenges presented by Beijing’s policies.

This will include building a positive transatlantic narrative, including on trade and investment, that is not only about China. It will require that the US look beyond the daily noise on China policy that is coming from 27 EU member states, remembering that Europe is not a monolith. And it will require that the administration and members of Congress are active, persistent, patient and when necessary forceful in making their policy arguments to European counterparts behind closed doors.

We are on a similar trajectory on China that has been driven by policy choices in Beijing. If Europe has a strong partner in Washington, I am convinced that Washington will have a strong partner in Europe.

***

The common front against China

The statements of the above cited two GMF-think-tank-members confirm the political goals: The lobbyists on the U.S. side are concerned with building a front against China together with Europe and drawing EU states into the conflicts of the Atlantic hegemon.

Bonnie S. Glaser holds the important position of executive director, GMF Indo-Pacific, with the organisation. She is additionally a Board Member on the U.S. Committee at the Council for Security Cooperation for Asia-Pacific and a member of the Council of Foreign Relations and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. She is also a Non-Resident Fellow at the Lowy Institute, Sydney, Australia and a Senior Associate at the Pacific Forum. Last but not least, Bonnie S. Glaser acts as a Senior Advisor for the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation.

Previously, she served as East Asia Consultant for the U.S. Department of Defence & State, as well as Senior Advisor for Asia and Director of the “China Power Project” at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Senior Associate of the CSIS International Security Program.

As Director of the China Power Project, Glaser appeared before the U.S. Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship Committee in 2019 on “Made in China 2025 and the Future of American Industry” to provide her assessment of the situation from the perspective of American interests.

Bonnie S. Glaser stated in general that GMF was acting bipartisan, but pursues an agenda that strongly aligns with the desires of her colleagues who appeared before U.S. Senate committees on June 7, 2023: To forge a coalition as broad as possible with countries to pull them over to the Atlantic side and perpetuate U.S. hegemony. GMF appears to be more of a transcontinental shadow operation to coordinate such activities.

The situation is reminiscent of that, some 20 years before World War I, when the United Kingdom (UK) and transnational masterminds looked for alliances to perpetuate their hegemonic course. This time, EU-Europe and Asian states are supposed to carry-over the hegemonic interests of the United States to China altogether, but supposed to completely forget their own interests in favour of Atlantic intentions.

A study by the Rhodium Group found-out, that a possible Chinese economic blockade of Taiwan could jeopardize $2 trillion worth of economic activity. Europe is currently painfully realizing what it means to be dragged into a war by Anglo-America, as is currently the case with Ukraine. This should be an impressive and clear warning not only to the EU states, but also to the states in Asia against the participation in other and more Atlantic adventures!

A contribution from Unser-Mitteleuropa Global Research

Einfach nur noch beängstigend und erschreckend.